As International Day to end Violence against sex workers is marked across the globe on 17th December http://www.december17.org/ we wanted to reflect on the continued high levels of targeted violence and hate crime committed against sex workers and also some of the changing trends in crimes experienced by sex workers as sex work itself changes, as do wider crime patterns. As Beyond the Gaze is focusing on the working conditions, safety and regulation of internet based sex work the safety and crime issues faced by people working in the online sector are very much on our minds.

Whilst it is important to stress that most commercial sex interactions go without harassment and violence research indicates that sex workers are more at risk from targeted harassment and violence than the general public and many other occupational groups – these risks varying according to sex working sectors, with many studies showing higher levels of violence against street sex workers. A systematic review of research on the correlates of violence against sex workers globally was carried out by Dr Kathleen Deering (University of British Columbia) and a team of researchers. This was published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2014 were they reported that workplace violence over a lifetime was recorded by 45 to 75% of sex workers, with 32% to 55% experienced violence in the last year.

We have researched violence against sex workers for some years and argued in an editorial for a special edition of Criminology and Criminal Justice in 2015 that within this global context it is important to unpack the nuances about which groups of sex workers experience violence, at what level and in what forms in order to appropriately develop laws and policies to prevent violence against sex workers .

In our research we have found that the relationship between sex work and violence is shaped by three key elements which allow for differences in the research evidence on the levels of violence between sectors and across different jurisdictions. Firstly, the environment /spaces in which sex work takes place, this acknowledges the different locational and organisational factors which shape safety across sectors. Secondly, the relationship to the state, that is where a particular form of sex work sits in the regulatory systems, it’s legal status, how and the extent to which it is criminalised and how those laws are enforced. For example, in legal frameworks that criminalise sex work or have quasi criminalisation with some activities associated with sex work criminalised, a difficult context is created where it is hard to gain sex worker confidence and trust in the police. When the police are involved in arresting sex workers, their clients or others who work with sex workers and are also the organisation sex workers must look to for protection and to report crime it is challenging for trust in the police to be achieved.

In our research we have found that the relationship between sex work and violence is shaped by three key elements which allow for differences in the research evidence on the levels of violence between sectors and across different jurisdictions. Firstly, the environment /spaces in which sex work takes place, this acknowledges the different locational and organisational factors which shape safety across sectors. Secondly, the relationship to the state, that is where a particular form of sex work sits in the regulatory systems, it’s legal status, how and the extent to which it is criminalised and how those laws are enforced. For example, in legal frameworks that criminalise sex work or have quasi criminalisation with some activities associated with sex work criminalised, a difficult context is created where it is hard to gain sex worker confidence and trust in the police. When the police are involved in arresting sex workers, their clients or others who work with sex workers and are also the organisation sex workers must look to for protection and to report crime it is challenging for trust in the police to be achieved.

Thirdly, stigma, social status, and the ‘othering’ of sex workers increases hostility and violence. There is a considerable consensus in the global sex work literature that sex workers are stigmatised and this is a central part of the ‘othering’ and objectification of sex workers which researchers have argued contributes to social exclusion, generates hostility and contributes to the denial of full rights and a lack of protection from victimisation. Findings from research show that adopting policing approaches which recognise crimes against sex workers as hate crime contributes to improving criminal justice responses to crimes against sex workers, hence we support such an approach. We support an intersectional approach to hate crime which recognises the varied experiences of hate crime that sex workers have, not only based on experiences of hostility and targeting by offenders because of their sex working but also other aspects of social identity such as race, nationality, gender and sexual identity. For example migrant sex workers may experience targeted crime related to their race or national identity intersected with their sex work status.

One of the reasons for 17th December is to remember those people in sex work who have been murdered. In the UK public imagination when sex worker murder is discussed, people tend to recall the serial murders of street sex workers such as the five women tragically murdered in Ipswich ten years ago, Gemma Adams, Tania Nichol, Anneli Alderton, Annette Nicholls and Paula Clennell. Since those murders in Ipswich 42 sex workers in the UK have been murdered who are recorded on the database maintained by National Ugly Mugs (NUM). If we take the period from October 2013 to the last (known) sex worker murder in the UK in February 2016 eighteen people have been murdered. Of these 56% worked indoor/online, 28% worked on the street. (Please note for 16% how they worked was recorded as not known in the NUM data base). Now compare this to UK sex workers murdered during 2007-2012 21 people were murdered, 71% worked on street, 24% worked indoor/online and 5% street and indoor, indicating an increase in the proportion of indoor/online sex workers who were murdered.

Since 17th December 2016 the NUM database records three murders of sex workers in the UK, Daria Pionko in Leeds, Georgina Symonds in Newport and Jessica McGrath in Aberdeen. Jessica and Georgina worked in escorting and Daria on the streets. So the issue of violence against sex workers and other crimes are very relevant for the online sector. Indeed as the online sector is the largest sector of the sex industry in UK it is no surprise that those who target sex workers also target people working in this sector.

This has also been highlighted by findings from a survey of 240 internet based sex workers funded by the Wellcome Trust carried out by our own Prof Teela Sanders in partnership with National Ugly Mugs in 2015. This found that some online sex workers reported crimes similar to sex workers in other sectors, but it also flagged up a number of crimes linked to online and digital technology which had been experienced by internet based sex workers. Some headline findings and recommendations from that research are;

- Levels of concern about crime varied: but 49% were either ‘fairly worried’ or ‘very worried’ about experiencing crime related to their sex work.

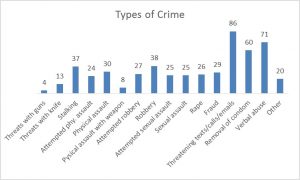

- 47% had experienced crime in their sex work – the types of which are shown in the chart below.

- For those working in the online sector new forms of targeted crime were evident. The most

common crimes experienced by those people who responded to the survey (86 out of 240) were digitally facilitated which included threatening & harassing texts/calls/emails plus verbal abuse.

common crimes experienced by those people who responded to the survey (86 out of 240) were digitally facilitated which included threatening & harassing texts/calls/emails plus verbal abuse. - Sex workers also reported incidents of robbery, rape, physical assault and attempted abduction. Removal of condoms without sex worker consent was the most commonly report non digital crime reported

- Half of respondents (49%) were either ‘unconfident’ or ‘very unconfident’ that the police will take crimes against them seriously

- Safety could be improved through decriminalisation, which would allow sex workers to work together, break down stigma , allow for development of improved trust in police and improved public protection policing for sex workers. The action that could improve safety most identified by sex workers taking part was decrimalisation.

If you want to read more about the research go to a summary https://beyond-the-gaze.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/InternetNUMBriefingFINAL2015.pdf or read ‘On our own terms’ published recently in Sociological Research Online http://www.socresonline.org.uk/21/4/15.html

The above post is written by Rosie Campbell and Teela Sanders. For more information and to connect with Rosie and Teela, follow them on twitter:

Dr. Rosie Campbell OBE – https://twitter.com/RosieCa27236598

Professor Teela Sanders – https://twitter.com/TeelaSanders